Israel and Egypt are too important to each other to just give up.

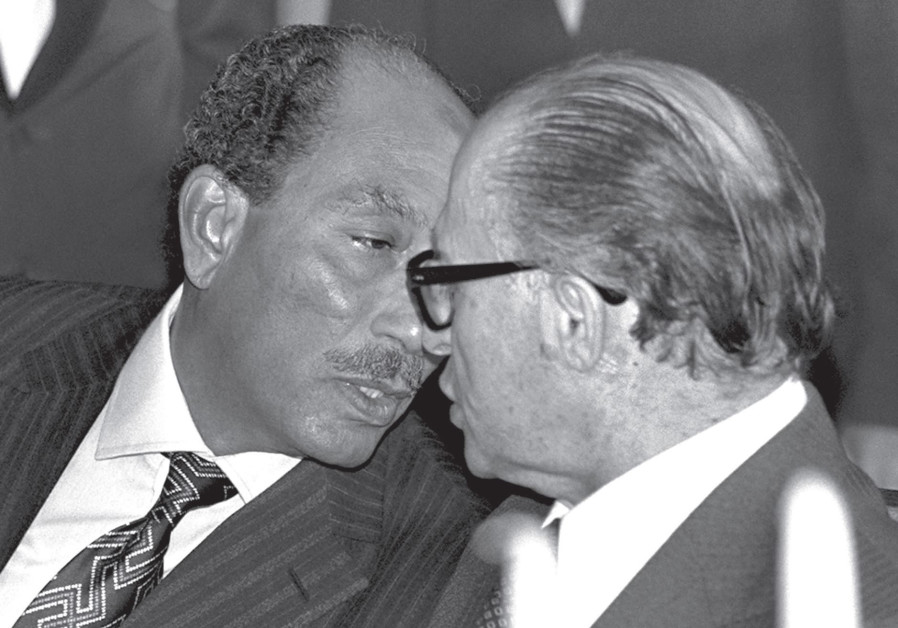

ANWAR SADAT and Menachem Begin chat during the former Egyptian president’s historic visit to Jerusalem in 1977. . (photo credit: REUTERS)

Israeli and Egyptian flags merged one into another were at the center of the stage, the president of Israel and others spoke about true friendship, true alliance, true hope. The festive ceremony that marked 40 years since Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s visit to Israel was inspiring indeed.

One small thing put a shade on an otherwise perfect event. Not even one guest from Egypt, apart from the honorable Ambassador Hazem Khayrat, was there to celebrate Sadat’s visit to Israel and the peace accord that followed. Not even one public event on that occasion took place in Cairo.

It’s important to stress that this necessary minimum includes military cooperation between the two frenemies.

During the last few years, since President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi took power in 2013, relations had improved dramatically. The extremely dangerous situation in northern Sinai obliged the leaders of the two countries to work together against the Islamist insurgency on the peninsula.

They also agreed to close ranks on specific issues related to security in Gaza, such as the tunnels that were used to smuggle weapons from Egypt to Gaza and terrorists from Gaza to Egypt. Never before had an Israeli prime minister and an Egyptian president worked so closely with each other, never before could their military discuss issues so freely and work together against security threats.

The representatives of the National Security Council who participated in one of the discussions on the issue at the Knesset actually said that they prefer the military aspect of relations to any other issue, noting the importance of security coordination between the two countries.

Does this mean that since military cooperation is going well, Israel can be satisfied with that and just let go of even a semblance of bilateral relations – diplomacy, commerce, culture etc.? It’s easy to wave off the discussion on normalization of relations with Egypt by stating that the peace with Egypt was always cold, while animosity toward the Jewish state was always the bon ton among the intellectuals and media. However, as it often happens in the Middle East, things can always get worse if unattended and in most cases, they will.

It seems that 40 years since the historical visit, the ice keeps piling on the already frosty relations between the two countries, which keep growing apart in all but one sense, the military. In any other aspect of relations, we witness a dangerous withdrawal from even modest successes of the past.

Today there is no connection between the civil societies – the anti-normalization vibe in Egypt is still very powerful. No academic cooperation is taking place, no visits of prominent intellectual figures such as Saad ad-Din Ibrahim or Ali Salem occur. The Israeli ambassador to Egypt was absent for nine months and returned to the country only after enormous efforts and long negotiations.

Trade between the two countries is non-existent, and even the QIZ (special free trade zones established in collaboration with Israel) are on decline. The Israeli businessmen who used to travel to Egypt regularly fear instability, and the Egyptian companies shy away from direct cooperation with Israel, afraid of backlash from boycott supporters in their own country.

The cooperation in natural gas production has become less promising as well, for the Egyptians have discovered their own enormous gas field. This discovery might jeopardize the already signed deals, but there is something more to it – the very negative attitude to this cooperation on the Egyptian street.

Tourism from Israel to Egypt has almost stopped due to security reasons and only the golden shores of southern Sinai experience a modest renaissance during the Jewish holidays.

And there is of course the media. After some timeout in anti-Israeli attacks, it seems that more and more outlets are going back to what they know so well – conspiracy theories where Israel plays the major roles, blaming Israel for cooperation with ISIS and what not.

All of that means that the circle of Egyptians who are exposed to Israel and Israelis is shrinking alarmingly – no trade, no academic exchange, no tourism, no civil society cooperation. The only Egyptians who get to work with Israelis come from very specific circles in the army, while everybody else is oblivious to Israel-Egypt relations.

Certainly, a renewal of negotiations with the Palestinians that would end in signing a peace treaty between the sides could jump-start the relations not only between Jerusalem and Cairo, but also among Jerusalem and Amman, Riyadh, Abu-Dabi and other Arab capitals. This would change the existing equation between Israel and the Arab world and provide a positive background for normalization.

The question is what will happen if there will be no progress between Israel and the Palestinians in the near future. What if the current situation of no-peace/no-war continues for a few more years? How would it affect the state of relations between Israel and its partners in the Arab world, Egypt and Jordan? There is no doubt that a serious move toward true normalization can only be made when something happens in the Palestinian arena, but until this occurs Israel must do much more. For this it will need a functioning and independent Ministry of Foreign Affairs, some perseverance and possibly some aid from the country that at the time negotiated the peace between Israel and Egypt, the United States.

The key actors in foreign policy in DC should be aware that today the Israeli-Egyptian peace is being emptied of its real meaning, that the situation is deteriorating despite the close military cooperation, and that some of it has to do with statesmen’s indifference to other components of the peace – trade, culture, civil society, diplomacy.

Israel and Egypt are too important to each other to just give up. Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat didn’t.

The writer is a member of Knesset for Zionist Union.